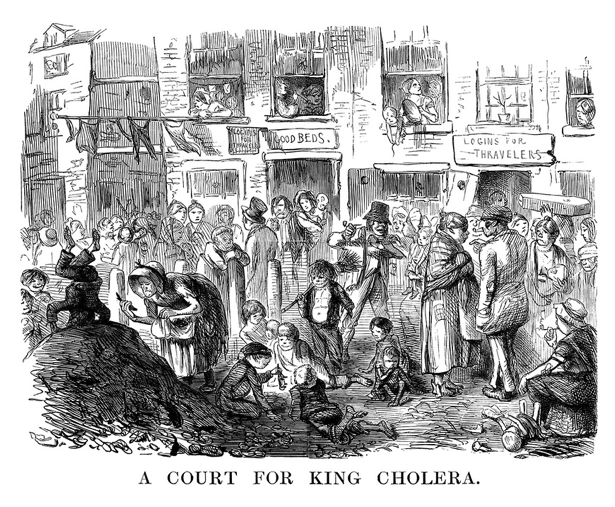

The outbreak of cholera in several of Britain’s largest cities provoked a discussion about the living conditions of the poor, especially in slums. The Punch magazine published a cartoon in 1852 titled ‘A Court for King Cholera’ to raise awareness of the disease, and the importance of general health and hygiene.[1] The cartoon was created with the purpose of shocking the viewer, with children playing amongst the waste, whilst others rummaged through it in the hope of finding something with some value. The Punch magazine had a large audience, and gave people the chance to see the slum. This cartoon was intended to provoke feelings of disgust and encourage people to question the importance of health and hygiene. Social investigative journalists and medical professionals found an interest in the amount of people living in slums who contracted the disease, causing the conditions of the slums to be investigated in more detail.

Within this cartoon, several issues which were thought to accelerate the spread of disease are highlighted. The terraced housing in the background, which often housed more than its capacity, lacked a proper sewage system and structure. The deteriorating conditions of housing caught the attention of social investigative journalist, Henry Mayhew, who dedicated much of his work to interviewing the slum. Miasma (bad air) was thought to cause the spread of disease, meaning that the presence of cesspools and sties in a heavily populated area was a major cause for concern. The disgusting living conditions of people in the slum were thought to be the cause of the outbreak of cholera, and inspired ideas for prevention, such as quarantine.[2]

Fig. 2“…But now the running brook is changed into a tidal sewer, in whose putrid filth staves are laid to season; and where the ancient summer-houses stood, nothing but hovels, sties, and muck-heaps are now to be seen.

Henry Mayhew, A Visit to the Cholera District of Bermondsey, The Morning Chronicle: Labour and Poor, 1849-1850

‘A Court for King Cholera’, also shows the activities of children in the slum. It is likely that the portrayal of children heightened the feelings of disgust, as in upper and middle class traditions, childhood and the preservation of a child’s innocence was deemed important. Alongside this, social journalist Henry Mayhew was concerned with the responsibilities of children in the community and the workplace.[3] This exposure to the lives of slum children played a major role in how the slum was viewed, and was featured in large amounts of literature and artwork. ‘A Court for King Cholera’ is a good example of this, the group of children playing amongst the pile of waste, whilst a child’s coffin is being carried through the background, demonstrates the consequences of slum life.

The concern for living conditions in slums was not always altruistic, and instead stemmed from the fear of diseases, such as cholera spreading to middle and upper class areas because of the poor.[4] This issue of housing conditions were exposed by many writers, which increased the pressure for the government to provide a solution. Connections between the locations of privies and slum dwellers, who contracted cholera, became more common. Dean Kirby writes about the first victim of cholera in Angel Meadow, who lived in a house with an overflowing privy situated at the back door.[5] It became undeniable that the sanitation in these areas were to blame for the outbreak of many diseases, including cholera. However, before any action could be taken, the extent of the problem needed to be documented so that plans could be made to improve housing and sewage systems.

This map shows the city of Leeds, and the relationship between the poor and cholera. The map highlights ‘bad streets’, workhouses and factories, whilst identifying areas where there has been a case of cholera. Mapping became extremely popular during the Victorian period as it was deemed a scientific way of documenting the population as well as its infrastructure. This map does not limit itself to documenting the poor, but also the whereabouts of the upper class. The areas where several blue dots appear, are areas in which are thought to cause or accelerate the outbreak of cholera. Unsurprisingly, these occur on most working-class streets. The table also shows the importance of overcrowding in an area, as where the population is more concentrated in one acre, the mortality rate is also higher. In areas I and II, the population per acre is 207, compared to the other areas which have figures of 118 and 84. However, areas I and II are those with the larger number of ‘bad streets’ and cholera fatalities.

Disgust occurs in many aspects of the slum, but disease was something that provoked feelings of disgust towards the slum nationwide. It was not only those living in the slum that were disgusted at the conditions they were forced to live in, but also social journalists who peaked the interests of the rest of the population, by demonstrating destitution and inefficiency.[6] Before the outbreak of epidemics such as cholera, it was not the responsibility of upper classes to question the living conditions of the poor, but cholera did not understand class. Disease does not recognise the difference between age, money or race, and without it the documentation of the slums would not have been so popular during the nineteenth century.

[1] Cruttenden, Aidan, The Victorians: English Literature in its Historical, Cultural and Social Contexts, (London: Evan Brothers Ltd., 2006), p.34

[2] Kirby, Dean, Angel Meadow: Victorian Britain’s Most Savage Slum, (Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2016), Chapter 5

[3] Jordan, Thomas E., Victorian Childhood: Themes and Variations, (SUNY Press, 1987)

[4] Thomas, Amanda J., Cholera: The Victorian Plague, (Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2015), p.85

[5] Drasar, B.S. & Forrest, B.D., Cholera and the Ecology of Vibrio Cholerae, (London: Chapman & Hall, 1996), p. 38-9

[6] Bronstein, Jamie L., & Harris, Andrew T., Empire State and Society, (John Wiley & Sons, 2012), p.117

Fig. 1 John Leech, ‘A Court for King Cholera’, Punch, (1852), Accessed online: https://punch.photoshelter.com/image/I0000_fVZ0QmMaPU

Fig. 2 Henry Mayhew, A Visit to the Cholera District of Bermondsey, The Morning Chronicle: Labour and Poor, 1849-1850

Fig. 3 Dr. Robert Baker, Report to the Leeds Board of Health- Sanitary Map of Leeds, (1833) Accessed online: http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/publichealth/sources/source5/mapofleeds.html